The Echoes of the Seven Rivers: A Journey through Vedic India #

Imagine yourself standing on the banks of a roaring river in 1500 BCE. The air is thick with the scent of burning ghee and wood smoke. You are not in the planned, brick-lined streets of the Harappan cities anymore; those have faded into the mists of the past. You are now stepping into the world of the Aryans—a world defined not by great monuments, but by great texts, powerful chants, and the thunder of chariot wheels.

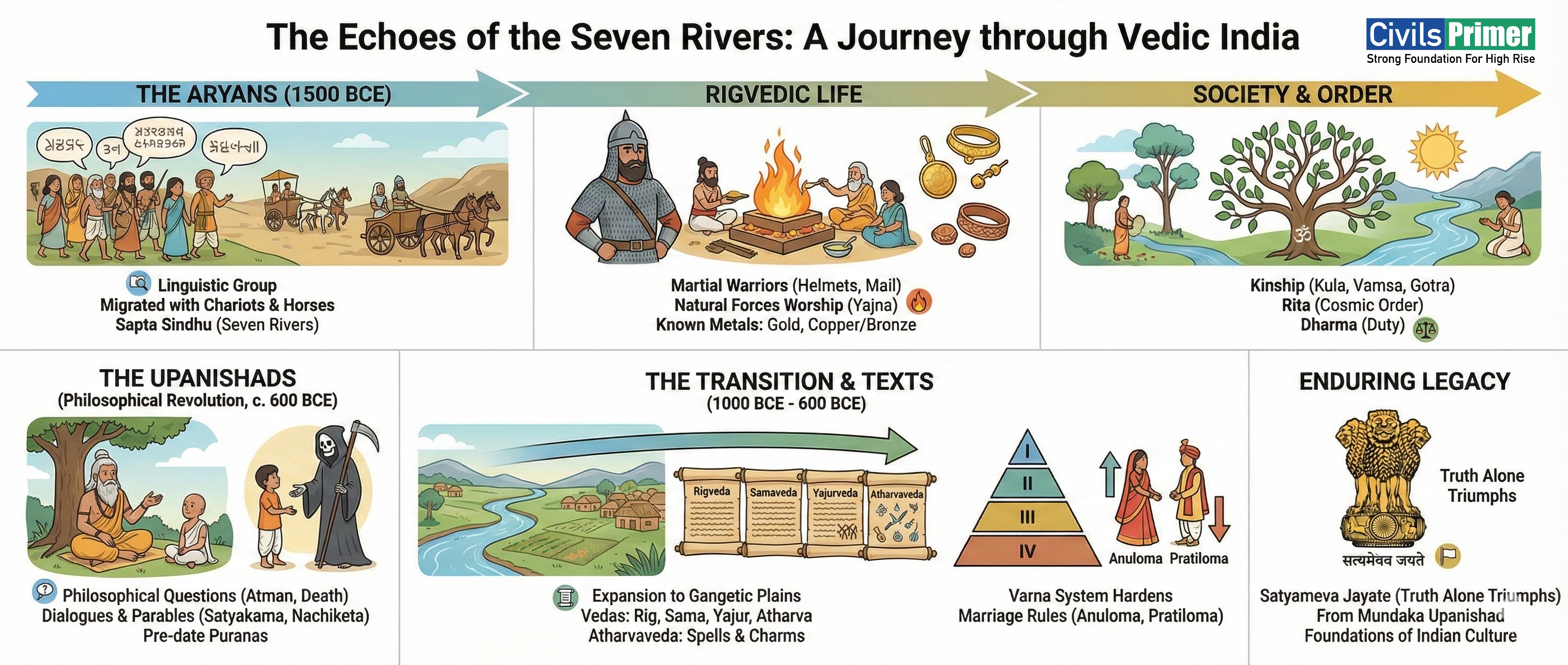

To understand this era, you must first understand who these people were. Forget the 19th-century notions of race. In the context of history, the term “Aryan” denotes a linguistic or speech group. They were a people bound by a common language—Indo-European—who migrated into the subcontinent, bringing with them a culture that would fundamentally shape the Indian ethos.

Part I: The Age of the Warrior-Pastoralists (The Rigvedic Period) #

As you look around this early landscape, the first thing you notice is the contrast between these newcomers and the people of the Indus Valley Civilization who came before them. The Indus people were traders and peace-loving urbanites. The Rigvedic Aryans? They were martial. If you looked closely at a Rigvedic warrior, you would see him geared for battle in a way the Harappans never were. Rigvedic Aryans used coats of mail and helmets in warfare, whereas the Indus Valley Civilization provides no evidence of their use.

Their material culture was also distinct. You might see a chieftain adorned with ornaments. Rigvedic Aryans knew gold, silver, and copper, while the Indus Valley Civilization did not know iron. It is important to remember this distinction: the Indus people knew copper and bronze, but they never smelted iron. The Aryans of the Rigveda knew gold (nishka) and copper/bronze (Ayas), but iron (shyama Ayas) would only become prominent in the later Vedic age.

But the greatest advantage the Aryans had was a beast that thundered across the plains. Rigvedic Aryans had domesticated the horse, whereas the Indus Valley people were not aware of it. While there are debates about isolated horse remains in Surkotada, the consensus is that the horse-centered culture—the chariot, the speed, the warfare—was a Vedic innovation, absent in the seal-centric culture of the Indus.

These Aryans settled in the land of the Sapta Sindhu (Seven Rivers). While the Ganga and Yamuna would become holy later, in these early days, they were on the periphery. The river most frequently mentioned in early Vedic literature is the Sindhu (Indus). It was the lifeline, the “river par excellence” that nurtured their pastoral economy.

Part II: The Cosmic Order and the Fire Altar #

Life in this period was governed by unwritten laws. As you sit by the sacrificial fire, the Yajna, you realize that their religion was not about temples or idols. Early Vedic religion primarily involved the worship of natural forces through yajnas. They looked at the wind, the rain, and the sun, and saw gods—Indra, Varuna, and Agni. They poured milk, grain, and ghee into the fire to appease these forces, seeking cattle, sons, and victory in return.

But holding this universe together were two profound concepts. The first was Rita. Imagine the sun rising every day, the rivers flowing downstream, and the seasons changing. This regularity wasn’t accidental. Rita represented the universal moral and cosmic order governing the universe. It was the law that even the gods had to obey.

The second concept was the duty of the human being within this order. Dharma in the Vedic context denoted the obligation and duty of an individual toward self and society. While Rita was the cosmic law, Dharma was the ethical conduct required to uphold it.

Society was organized through kinship. You belonged to a family (Kula), a lineage (Vamsa), or a clan (Gotra). However, if you were looking for the state’s financial organization, you would look for a different term. The term “Kosa” refers to treasury and does not belong to the kinship-related group of Kula, Vamsa, and Gotra. This is a crucial distinction for your exam: Kosa is administrative; the others are social.

Women in this early period held a status of respect. They were educated and participated in assemblies. One such luminary shines through the texts: Lopamudra was a Brahmavadini who composed hymns of the Vedas. She, along with others like Gargi and Maitreyi, proves that the composition of sacred texts was not the sole preserve of men.

Part III: The Transition and the Texts #

As centuries passed (moving from 1500 BCE to 1000 BCE and beyond), the Aryans moved eastward into the Gangetic plains. The texts expanded. The Rigveda was followed by the Sama, Yajur, and Atharva Vedas.

The tone of the literature changed. While the Rigveda was full of praise for the gods, the fourth Veda addressed the anxieties of daily life. The Atharvaveda contains hymns related to magical charms and spells. It dealt with warding off evil spirits, curing diseases, and handling domestic strife—a fascinating glimpse into the common person’s beliefs.

Social stratification also became more rigid. The fluid social classes hardened into the Varna system. Marriage rules became strict. The Chandogya Upanishad discusses forms of marriage such as Anuloma and Pratiloma. Anuloma (hypergamy) was the marriage of a man from a higher varna to a woman of a lower varna, which was generally accepted. Pratiloma (hypogamy), where a woman of higher varna married a man of lower varna, was discouraged.

Part IV: The Philosophical Revolution (The Upanishads) #

Towards the end of the Vedic period (around 600 BCE), a new wave of thinking emerged. People began to ask questions that rituals couldn’t answer: What happens after death? What is the nature of the soul (Atman)?

This led to the composition of the Upanishads (also known as Vedanta). It is important to get the chronology right: The Upanishads were composed earlier than the Puranas. The Puranas, with their elaborate myths of the trinity (Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva), came much later during the Gupta and post-Gupta periods. The Upanishads were the philosophical climax of the Vedic age.

These texts were not dry academic thesis; they were dialogues and stories. The Upanishads contain parables, including the story of Satyakama Jabala. Satyakama was a boy who did not know his father’s name, yet he was accepted as a student by a sage because of his commitment to the truth—a powerful parable challenging birth-based discrimination.

Another famous dialogue regarding the mystery of death took place between a young boy and the Lord of Death himself. The dialogue between Nachiketa and Yama appears in the Kathopanishad. In this text, Yama teaches Nachiketa that the soul is unborn and undying, a core concept of Hindu philosophy.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy #

As we step back from this ancient world, we see that its echoes are still present in modern India. When you look at the National Emblem of India today, you see the words “Truth Alone Triumphs.” The national motto “Satyameva Jayate” is derived from the Mundaka Upanishad.

From the galloping horses of the Rigveda to the deep philosophical inquiries of the Upanishads, the Vedic age laid the foundational stones of Indian culture. For you, the aspirant, remembering these distinctions—between the helmet-wearing Aryan and the peaceful Harappan, between the ritualistic Vedas and the philosophical Upanishads—is the key to mastering this chapter of history.

Mains PYQs #

- Question: Give a comparative analysis of the different aspects of Rig Vedic and Later Vedic Ages, emphasising on social, political, economic, and religious aspects.

- Question: To what extent did the word ‘gau’ hold significance in the lives of Rig Vedic people. Explain, giving suitable examples.

- Question: Discuss certain aspects of Vedic Age (both Rig Vedic and Later Vedic) vis-a-vis the Indus Valley civilisation. Are they similar or dissimilar? Conduct suitable analysis

Answer Writing Minors #

Common Introductions (Choose one based on the question context)

- Option 1 (General/Historical Context): “The Vedic Age (c. 1500–600 BCE) marks a pivotal transition in Indian history following the decline of the Harappan Civilization. Characterized by the migration of Indo-Aryan speakers into the Sapta Sindhu region and later the Gangetic plains, this era is reconstructed primarily through Vedic literary corpus, laying the foundational socio-political and religious structures of ancient India.”

- Option 2 (Social/Cultural Context): “Spanning a millennium (c. 1500–600 BCE), the Vedic Period represents the formative phase of Indian culture, witnessing a gradual shift from a semi-nomadic, pastoral tribal society (Jana) to a settled, agrarian, and stratified territorial state (Janapada). This evolution is distinctively marked by the composition of the Vedas, Brahmanas, and Upanishads, which provide deep insights into the Aryans’ material and spiritual life.

Common Conclusions (Choose one based on the question context)

- Option 1 (Focus on Political/Economic Transition): “In conclusion, the Vedic Age was a crucible of change that transformed the Indian subcontinent from a pastoral, egalitarian tribal setup into a complex, agrarian, and varna-divided society. This consolidation of territorial authority (Rashtra) and the use of iron technology paved the way for the ‘Second Urbanization’ and the rise of the Mahajanapadas in the 6th century BCE.”

- Option 2 (Focus on Religion/Philosophy): “Ultimately, the Vedic period left an enduring legacy, evolving from the ritualistic worship of natural forces in the Rig Veda to the profound philosophical inquiries of the Vedanta (Upanishads). While it institutionalized social stratification, its intellectual climax challenged priestly domination, setting the stage for the emergence of heterodox sects like Buddhism and Jainism