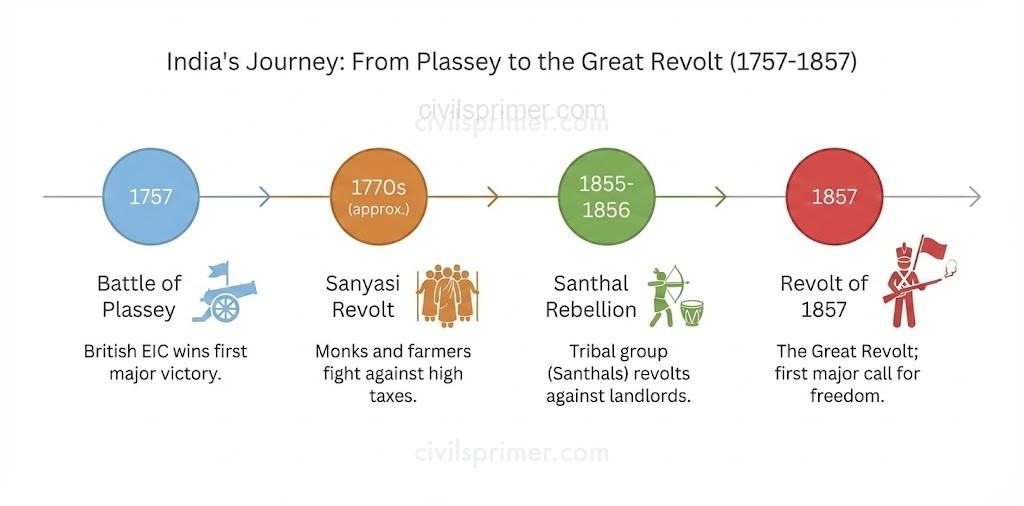

India’s Fight for Freedom (1757–1858): The Sparks Before the Fire #

History often remembers 1857 as the first major blow to British rule. But the truth is, the British conquest was never a smooth affair. From the moment the East India Company (EIC) began transforming from traders to rulers, they faced fierce resistance. The silence of the countryside was deceptive; beneath it, a lava of discontent was boiling for a hundred years, fueled by displaced zamindars, starving peasants, and tribal communities whose forests were stolen. This is the story of those early sparks that eventually ignited the great fire of 1857.

Part 1: Civil Uprisings – The Rumble in the Villages #

Imagine the Bengal of the late 18th century. The famine of 1770 had wiped out one-third of the population, yet the Company’s tax collectors were relentless. This desperation birthed the Sanyasi-Fakir Rebellion (1763–1800). These were not just wandering ascetics; they were a mix of peasants, dispossessed zamindars, and disbanded soldiers. Led by figures like Majnum Shah and Debi Chaudhurani, they raided Company factories and treasuries. It took Warren Hastings nearly four decades to suppress them.

In Odisha, a different storm was brewing. The Paika Rebellion (1817) was led by the traditional landed militia of the region, the Paiks. When the British took over Odisha in 1803, they imposed extortionist land revenue policies and taxes on salt, ruining the Paiks. Under Bakshi Jagabandhu, the military chief of the Raja of Khurda, the Paiks rose up, forcing the British to retreat temporarily. Though brutally repressed by 1818, it remains a powerful symbol of regional resistance.

Part 2: Tribal Revolts – The Forest Fights Back #

While the plains burned, the forests were not quiet. The tribals, or Adivasis, lived in relative isolation, managing their own affairs. The British introduced a hated trinity into their lives: the Sahukar (moneylender), the Trader, and the Company Official. These outsiders were collectively called Dikus.

The Kol Mutiny (1831): In the Chotanagpur region (modern Jharkhand), the transfer of tribal lands to Sikh and Muslim farmers and money-lenders enraged the Kols. Led by Buddho Bhagat, they killed or burnt a thousand outsiders. It took large-scale military operations to restore order.

The Santhal Hool (1855–56): Perhaps the most massive tribal insurrection was the Santhal Rebellion. The Santhals had settled in the Damin-i-koh (skirts of the Rajmahal hills) to practice agriculture. But they soon found themselves trapped in debt to diku moneylenders and oppressed by the police. Under the leadership of two brothers, Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu, thousands of Santhals armed with bows and arrows declared the end of Company rule. They targeted zamindars, moneylenders, and railway engineers. The British crushed the rebellion with elephants and muskets, killing nearly 20,000 Santhals. However, the ferocity of the movement forced the British to create a separate Santhal Pargana to protect their rights.

The Bhil Uprisings (1817–19): In the Western Ghats (Khandesh), the Bhils revolted against the new British master who threatened their agrarian rights. Although the British used both force and conciliatory measures, the Bhils rose again multiple times in the 19th century.

Part 3: The Great Revolt of 1857 – The Storm Breaks #

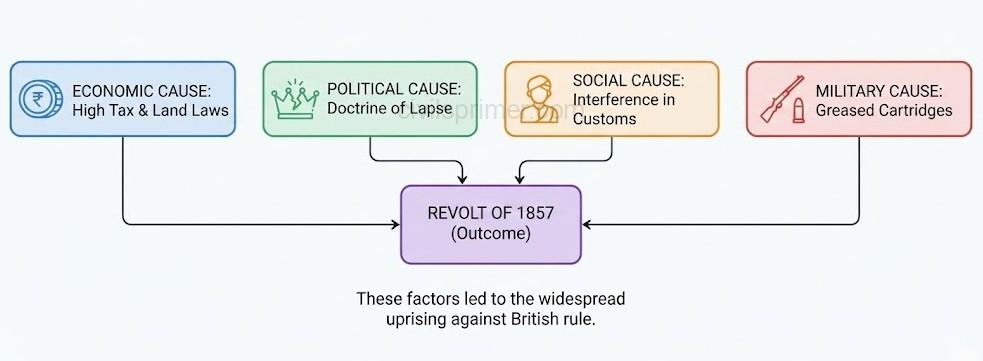

By 1857, the discontent was no longer local. It was universal. The Company had alienated almost every section of Indian society.

Why did they Rebel? (The Causes)

1. Political Insecurity: Lord Dalhousie’s Doctrine of Lapse was a masterstroke of imperial theft. States like Satara, Jhansi, and Nagpur were annexed simply because the ruler died without a natural male heir. In 1856, Awadh was annexed on grounds of “misgovernance,” leaving thousands of nobles and soldiers unemployed,.

2. Economic Ruin: The peasantry was crushed under heavy taxation. The artisans were destroyed by the influx of British machine-made goods. The sepoy was merely a “peasant in uniform,” and the suffering of the rural family was felt in the army barracks,.

3. Socio-Religious Fear: The activities of Christian missionaries and laws like the Religious Disabilities Act (1856) made Indians fear that the British aimed to convert them to Christianity,.

4. The Military Spark: The immediate trigger was the Enfield Rifle. The cartridges were greased with cow and pig fat, offending both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. When soldiers at Meerut refused to use them, they were jailed. This was the last straw,.

Part 4: Revolt Centers and Leaders – The March to Delhi #

On May 10, 1857, the sepoys at Meerut broke open the jails, killed their officers, and marched to Delhi.

- Delhi: The rebels proclaimed the aged Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, as the Emperor of India. He became the symbolic head, though the real command lay with General Bakht Khan.

- Kanpur: Nana Saheb, the adopted son of the last Peshwa (who was denied his pension), expelled the British and declared himself Peshwa.

- Lucknow: Begum Hazrat Mahal led the revolt, proclaiming her son Birjis Qadir as the Nawab. Peasants and sepoys besieged the British Residency.

- Jhansi: The widowed Rani Laxmibai, wronged by the Doctrine of Lapse, refused to surrender her territory. She famously declared, “Main apni Jhansi nahin doongi” (I shall not give up my Jhansi). She was joined by Tantia Tope.

- Bihar: Kunwar Singh, an 80-year-old zamindar of Jagdishpur, led the rebels. He nursed a grudge because the British had deprived him of his estates.

Part 5: The Revolt – The Fall and the Aftermath #

Despite their courage, the rebels failed. Why?

1. Lack of Unity: There was no central command. Nana Saheb, the Rani of Jhansi, and Bahadur Shah fought for their own territories, lacking a unified modern nationalist ideology.

2. Missing Support: The revolt was largely limited to North India. The Madras and Bombay armies remained loyal. The intelligentsia, princes like Scindia of Gwalior and the Nizam of Hyderabad, and merchants did not support the rebels, acting as “breakwaters to the storm”,.

3. Superior British Resources: The British had the telegraph, better weapons (the Enfield Rifle!), and able generals like Lawrence, Outram, and Havelock.

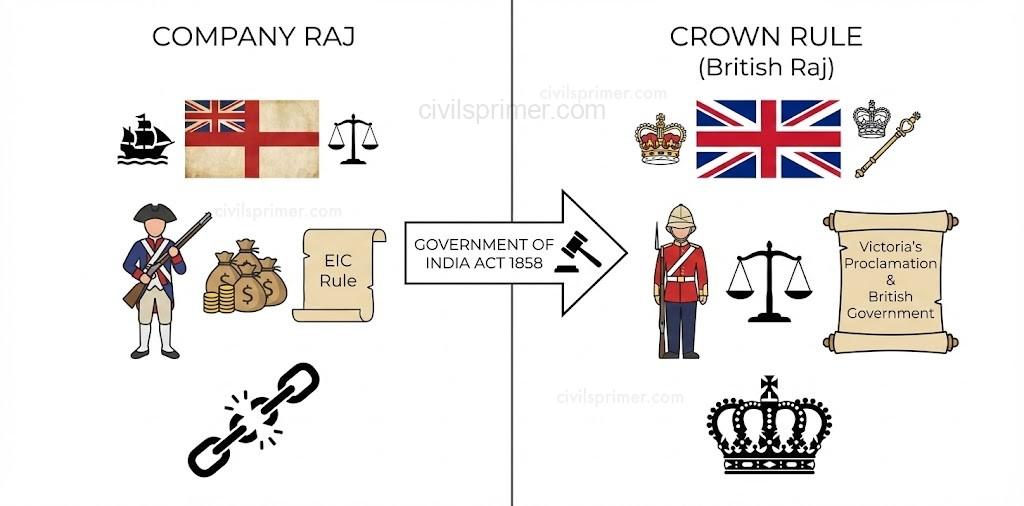

The Aftermath: A New Era The revolt was brutally suppressed by 1859. But the Company’s rule was dead.

- Government of India Act, 1858: The power to govern India was transferred from the East India Company to the British Crown. The Governor-General was now the Viceroy (Lord Canning was the first).

- Queen’s Proclamation (1858): It promised no further territorial expansion, respect for the rights of native princes, and non-interference in religious practices. The era of annexation ended; the era of “Divide and Rule” began.

The revolt was not just a mutiny; it was a violent shaking of the imperial foundation that sowed the seeds of nationalism for the future.

UPSC Mains Subjective Previous Years Questions #

- 2019 → The 1857 Uprising was the culmination of the recurrent big and small local rebellions that had occurred in the preceding hundred years of British rule. Elucidate.

- 2016 → Explain how the Uprising of 1857 constitutes an important watershed in the evolution of British policies towards colonial India.

- 2013 → Defying the barriers of age, gender, and religion, Indian women became the torch-bearers during the struggle for freedom in India. Discuss.

- 1999 → ‘What began as a fight for religion ended as a war of independence, for there is not the slightest doubt that the rebels wanted to get rid of the alien government and restore the old order of which the king of Delhi was the rightful representative.’ Do you support this viewpoint?

Answer Writing Minors #

(For Mains Answers on Administrative/Economic Policies)

- Introduction: The establishment of British rule in India marked a structural shift from a trade-mercantilist relationship to a colonial economy characterized by the systematic subordination of Indian interests to British imperial needs. Through instruments like the Land Revenue Settlements and the introduction of a monolithic administrative structure (Civil Services, Police, and Judiciary), the colonial state fundamentally altered the socio-economic fabric of the subcontinent.

- Conclusion: Ultimately, these administrative and economic policies created a “colonial modernization” that unified India administratively but impoverished it economically through De-industrialization and the drain of wealth. While the “steel frame” of administration provided stability, it served as a vehicle for extraction, leaving a legacy of poverty and structural bottlenecks that independent India had to struggle to overcome.

Related Latest Current Affairs #

- October, 2025: Protests involving Manki-Munda System and Kol Revolt (1831-32) Protests by the Ho tribe in Jharkhand highlighted the Manki-Munda self-governance system. This system was codified under Wilkinson’s Rules (1833) by the British following the Kol revolt (1831-32) and early Ho uprisings to co-opt tribal governance into the colonial administration.

- October, 2025: Red Fort and the 1857 Revolt Connection Following a blast near the Red Fort, its historical significance was revisited. Built by Shah Jahan, it became a key site during the First War of Independence (1857), where the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was captured and tried by the British before being exiled.

- October, 2025: Documentation of Bhil Tribe’s History of Resistance The Tribal Affairs Ministry released a collection of Bhil folk tales. The Bhils, one of India’s oldest tribes, fought guerrilla wars against the British to defend their lands and were subsequently branded a “criminal tribe” under the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871 due to their resistance.

- July, 2025: Controversy Over Paika Rebellion (1817) in Textbooks A political backlash occurred after NCERT textbooks omitted the Paika Rebellion (1817) of Odisha. Led by Bakshi Jagabandhu, this armed uprising against British land revenue policies and the salt monopoly is often cited as the “First War of Independence,” predating 1857.

- July, 2025: 170th Anniversary of the Santhal Rebellion (Hul) The 170th anniversary of the Santhal Rebellion (1855–56) was observed as ‘Hul Diwas’. Led by Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu, this massive uprising in the Rajmahal hills was directed against British colonial oppression, the zamindari system, and moneylenders, serving as a precursor to the 1857 revolt.