The Iron Grid: How the Company Built a State #

Imagine a massive corporate entity, not unlike a modern tech giant, but with guns, ships, and the power to levy taxes. This was the East India Company (EIC). From 1757 to 1857, this trading body transformed into a sovereign power, weaving a net of laws, steel rails, and bureaucracy over the Indian subcontinent. This is the story of that transformation—the building of the “British Raj.”

Constitutional Developments: Taming the Leviathan #

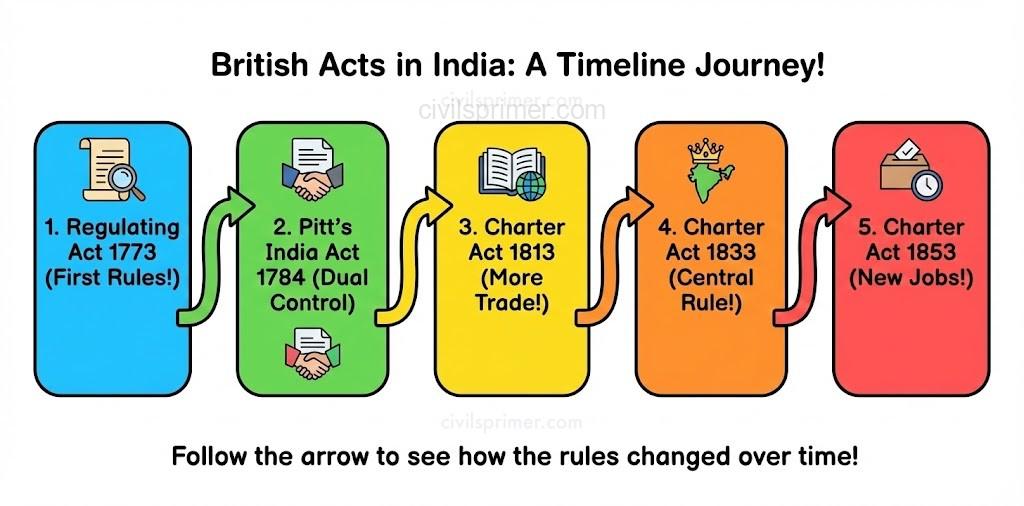

By the 1770s, the Company was rich, but its officers were corrupt, and the Company itself was facing bankruptcy. The British Parliament decided it was time to rein in this “merchant-ruler.” The first step was the Regulating Act of 1773. It was the first time the British Parliament recognized the political functions of the Company. It elevated the Governor of Bengal to the Governor-General of Bengal (Warren Hastings was the first) and established a Supreme Court at Calcutta. However, it created a chaotic system where the Governor-General was often held hostage by his own council.

To fix this, the Pitt’s India Act of 1784 was introduced. It created a “Double Government.” The Company handled commerce, but a new Board of Control in London handled civil, military, and revenue affairs. The Company was now a subordinate department of the British State. As the 19th century dawned, the Industrial Revolution in Britain demanded markets. The Charter Act of 1813 ended the Company’s monopoly on trade in India (except for tea and trade with China) and allowed Christian missionaries to enter India,. It also set aside ₹1 lakh for education—a humble beginning for modern education.

The grip tightened with the Charter Act (1833). This was the final step toward centralization. The Governor-General of Bengal became the Governor-General of India (William Bentinck was the first). The Company lost its monopoly entirely, becoming a purely administrative body. A Law Member (Macaulay) was added to the council to codify Indian laws. Finally, the Charter Act (1853) separated the executive and legislative functions of the Governor-General’s council, creating a mini-parliament. Crucially, it introduced open competition for the Civil Services, ending the Company directors’ patronage.

Administrative Pillars: The Steel Frame #

To rule such a vast land, the British needed more than just laws; they needed machinery.

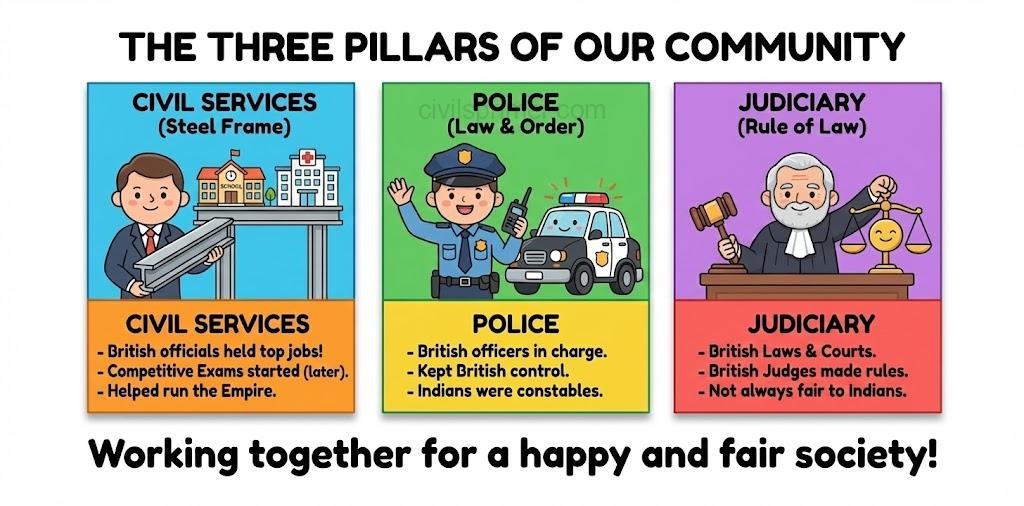

1. The Civil Services: Initially, “civil servants” were just traders. Lord Cornwallis is considered the father of the Civil Services in India. He tried to check corruption by raising salaries and strictly enforcing rules against private trade. He Europeanized the administration, believing “Every native of Hindustan is corrupt”. Later, Lord Wellesley established Fort William College (1800) to train young recruits, though training was later moved to Haileybury College in London,.

2. The Police: Before the British, policing was the duty of Zamindars. Cornwallis changed this. He relieved Zamindars of police duties and established Thanas (circles) headed by a Daroga. However, the police became a scourge to the people, often indulging in corruption and oppression. Later, William Bentinck abolished the office of the SP, but the system remained inefficient until the Police Act of 1861.

3. The Judiciary: The story of the judiciary is one of evolution. Warren Hastings set up Diwani Adalats (civil) and Fauzdari Adalats (criminal) at the district level. Cornwallis separated the executive from the judiciary, famously stripping the Collector of judicial powers. He established a gradation of courts. Later, William Bentinck abolished the mobile Circuit Courts and made Persian optional, introducing English as the official language in Supreme Courts. In 1833, a Law Commission under Macaulay codified the laws, leading to the IPC and CrPC.

Revenue Systems: The Burden of Land #

The primary motive of the Raj was revenue. To maximize this, they experimented with three major land systems.

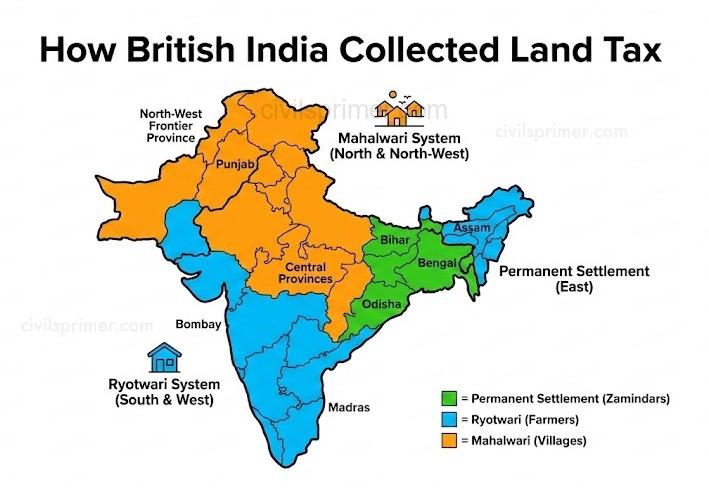

1. Permanent Settlement (1793): Introduced by Lord Cornwallis in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. The Zamindars were made owners of the land, and the revenue they had to pay to the state was fixed forever (permanently).

The Trap: The “Sunset Law” meant if a Zamindar failed to pay by sunset on a specific day, his estate was auctioned.

The Result: It created a class of loyal landlords but ruined the cultivators, who were reduced to tenants-at-will. It led to absentee landlordism.

2. Ryotwari System (1820): In the South (Madras and Bombay), there were no big Zamindars. Thomas Munro and Alexander Read devised a system to collect revenue directly from the Ryots (cultivators).

The Reality: While it aimed to remove intermediaries, the high revenue demand (often 50%) and the rigidity of collection meant the state effectively became a giant Zamindar. Peasants often had to resort to moneylenders.

3. Mahalwari System (1822): In the North-West Provinces and Punjab, the village community was strong. Holt Mackenzie introduced a system where the revenue was settled with the village community or Mahal collectively.

The Flaw: The village headmen (Lambardars) became powerful, and the heavy revenue demand led to widespread dispossession of land.

Economic Impact: The Great Drain #

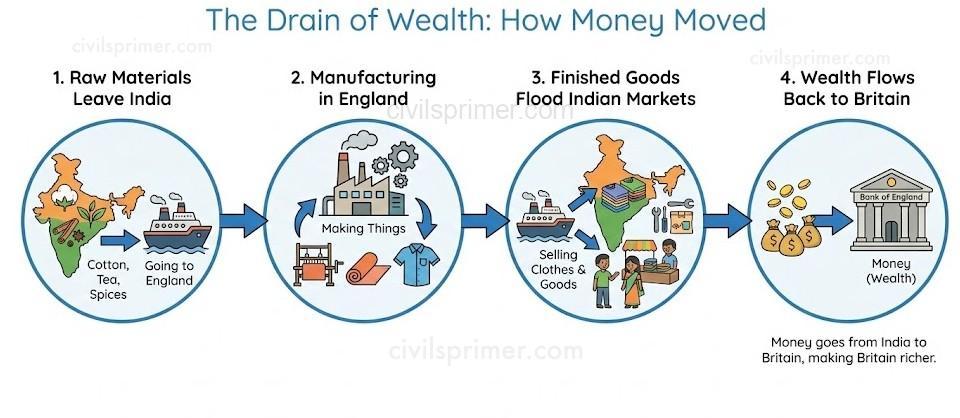

The economic story of British India is one of De-industrialization. Before the British, India was the “sink of precious metals,” exporting fine textiles. The Industrial Revolution in England changed everything.

- One-Way Free Trade: After 1813, cheap machine-made British textiles flooded India, while Indian goods faced high tariffs in Britain. The Indian handloom weavers were ruined. William Bentinck famously noted, “The bones of the cotton weavers are bleaching the plains of India”.

- Commercialization of Agriculture: Farmers were forced to grow cash crops like indigo, cotton, and opium instead of food grains to feed British industries. This linked Indian agriculture to global market fluctuations.

- Drain of Wealth: Nationalists like Dadabhai Naoroji and R.C. Dutt exposed how India’s wealth—salaries, pensions, home charges—was being siphoned off to Britain without any return.

Famines and Poverty: The culmination of these policies was poverty. The shift to cash crops and the lack of state support led to horrific famines. The Bengal Famine of 1769-70 wiped out one-third of the population. Between 1850 and 1900, nearly 2.8 crore people died in famines.

The Railways (1853): Lord Dalhousie introduced the railways, ostensibly for development. However, the tracks were laid primarily to mobilize the army and to extract raw materials from the hinterland to the ports. It served the empire first, and the people second.

By 1857, the stage was set. The administrative steel frame was in place, the economy had been hollowed out, and the resentment of the people—peasants, sepoys, and zamindars—was boiling over.

UPSC Mains Subjective Previous Years Questions #

- 2022 → Why was there a sudden spurt in famines in colonial India since the mid-eighteenth century? Give reasons.

- 2017 → Examine how the decline of traditional artisanal industry in colonial India crippled the rural economy.

- 2014 → Examine critically the various facets of economic policies of the British in India from mid-eighteenth century till independence.

Answer Writing Minors #

- Introduction (For Mains Answers):

The establishment of British rule in India marked a structural shift from a trade-mercantilist relationship to a colonial economy characterised by the systematic subordination of Indian interests to British imperial needs. Through instruments like the Land Revenue Settlements and the introduction of a monolithic administrative structure (Civil Services, Police, and Judiciary), the colonial state fundamentally altered the socio-economic fabric of the subcontinent. - Conclusion (For Mains Answers):

Ultimately, these administrative and economic policies created a “colonial modernization” that unified India administratively but impoverished it economically through De-industrialization and the drain of wealth. While the “steel frame” of administration provided stability, it served as a vehicle for extraction, leaving a legacy of poverty and structural bottlenecks that independent India had to struggle to overcome.

Related Latest Current Affairs #

- October, 2025: Revisiting Colonial Administrative Policies in Tribal Areas (Wilkinson’s Rules, 1833) Protests involving the Ho tribe in Jharkhand brought attention to the Manki-Munda system, which was codified under Wilkinson’s Rules in 1833. This colonial administrative policy was designed by the British to co-opt tribal self-governance into the imperial administration following early tribal revolts like the Kol uprising.

- October, 2025: Centenary of UPSC and Evolution of Civil Services (1854–1926) As the Union Public Service Commission marked its centenary, discussions traced the history of the “Steel Frame” back to the Macaulay Committee Report (1854). This report replaced the East India Company’s patronage system with a merit-based competitive examination, marking a pivotal shift in the administrative policy of the British Raj.

- August, 2025: Debate on the “Colonial Steel Frame” of Bureaucracy Editorials titled “Breaking the Colonial Steel Frame” analysed the persistence of the Westminster-style bureaucracy established during the Company rule. The discourse highlighted how the current administrative structure still reflects the control-oriented framework designed for colonial administration rather than development.

- July, 2025: 170th Anniversary of the Santhal Rebellion (Hul) (1855) The observance of ‘Hul Diwas‘ commemorated the Santhal Rebellion (1855–56), a massive uprising triggered by the Permanent Settlement (Zamindari) system. The event highlighted the severe economic impact of British revenue policies, which emboldened moneylenders and landlords to exploit tribal peasants, serving as a precursor to the 1857 revolt.

- July, 2025: Controversy Over Paika Rebellion (1817) Omission Political backlash emerged after NCERT textbooks omitted the Paika Rebellion (1817) of Odisha. This armed revolt was a direct response to British land revenue policies, including the resumption of hereditary rent-free lands and currency reforms that devastated the local economy.

- February, 2025: Review of the Zamindari System and Lord Cornwallis’s Policies Legal and historical discussions revisited the Permanent Settlement Act (1793) introduced by Lord Cornwallis. The analysis focused on how this land revenue system created a class of intermediaries (Zamindars) vested with absolute ownership, leading to the systemic exploitation of peasants and stagnation of agriculture.