Syllabus Link

Prelims: Constitutional Articles (246A, 279A, 293), GST Council structure, recent slab rates, cessation of Compensation Cess.

Mains (GS II & III): Centre-State Financial Relations, Fiscal Federalism, Borrowing Powers of States, Tax Reform Impact.

Introduction & Basics

The Goods and Services Tax (GST), introduced via the 101st Constitutional Amendment Act, was envisioned as a “One Nation, One Tax” system to unify India’s market. However, it fundamentally altered the federal fiscal equilibrium by subsuming state powers to levy indirect taxes. The September 2025 GST Council decision to move to a two-tier rate structure (5% and 18%) and abolish the Compensation Cess marks the start of “GST 2.0.” While these reforms aim to simplify taxation, they—along with the legal battles over state borrowing limits (Kerala case)—have reignited the debate on the fiscal autonomy of States versus the macroeconomic stability managed by the Centre.

Constitutional and Legal Framework of GST Reforms

Fiscal Federalism: The division of financial powers and responsibilities between the Union and States. In India, it is heavily tilted towards the Centre (Vertical Imbalance) to ensure equity, but States have higher expenditure responsibilities.

Article 246A: Grants simultaneous power to the Union and State legislatures to make laws on GST.

Article 279A: Constitutes the GST Council, a joint forum where the Centre (1/3rd vote weight) and States (2/3rd vote weight) decide on rates and exemptions. A 3/4th majority is required for decisions, granting the Centre a virtual veto.

Article 293(3): A State cannot raise a loan without the consent of the Centre if it has any outstanding loan owed to the Centre. This is the crux of the borrowing limit debate.

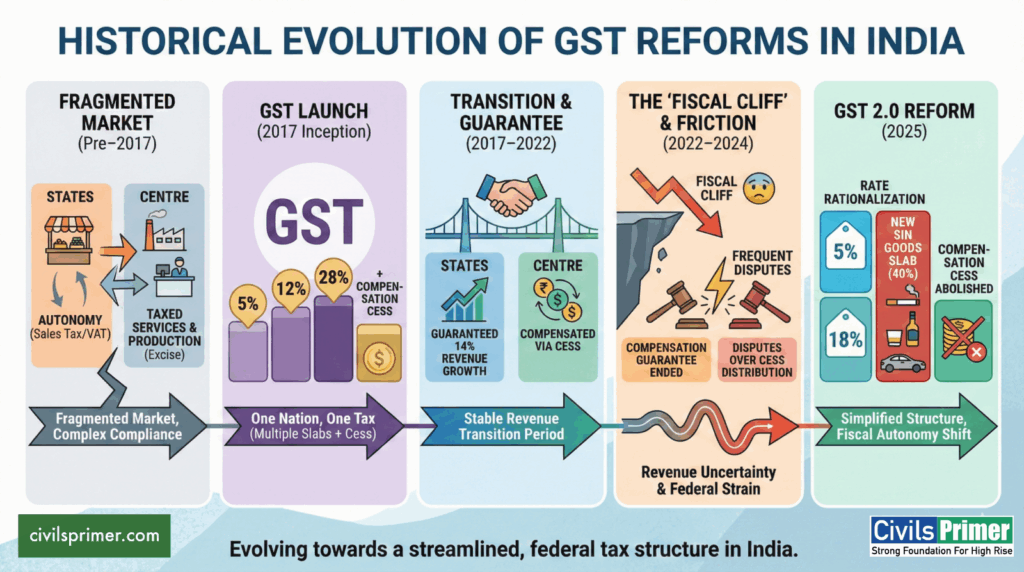

Historical Evolution & Journey of GST Reforms

- Pre-2017: States had autonomy over Sales Tax/VAT; Centre taxed Services and Production (Excise). Fragmented market.

- 2017 (Inception): GST launched with multiple slabs (5, 12, 18, 28%) + Compensation Cess.

- 2017–2022 (Transition): States guaranteed 14% revenue growth; compensated by Centre via Cess.

- 2022–2024 (Friction): Compensation guarantee ended; States faced “fiscal cliff.” Frequent disputes over Cess distribution.

- 2025 (Reform): Rate rationalization to 5% and 18%; 40% “Sin Goods” slab introduced; Compensation Cess abolished.

Case Studies: Lessons in Federal Dynamics

| Case Study | Context & Event | Why it Matters (Lessons) |

| State of Kerala v. Union of India (2023-2025) | Kerala challenged the Centre’s imposition of a Net Borrowing Ceiling (NBC). The Centre included “off-budget borrowings” (loans taken by state PSUs like KIIFB) within the state’s borrowing limit, drastically reducing Kerala’s fiscal space. | Lesson: Highlights the tension between Fiscal Discipline (Centre’s goal) and Developmental Autonomy (State’s need). It clarifies that Article 293 gives the Centre significant control over sub-national debt to prevent fiscal profligacy. |

| The Compensation Cess Saga (2020-2025) | During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centre initially struggled to pay the guaranteed compensation to states, citing an “Act of God.” States were asked to borrow. The Cess was later extended to repay loans. | Lesson: Exposed the fragility of trust in federal relations. It showed that statutory guarantees (GST Compensation Act) can falter under economic stress, necessitating a more robust, constitutionally protected revenue-sharing mechanism. |

Analysis of Recent GST Reforms (2025 Decisions)

- The Two-Tier Structure (5% & 18%):

- Pros: Reduces litigation (classification disputes), lowers compliance burden for MSMEs, and likely reduces inflation on essential goods.

- Cons: States lose the flexibility to tax “merit goods” at a middle rate (12%); revenue neutrality is uncertain in the short term.

- Abolition of Compensation Cess:

- Impact: Removes the “guaranteed” safety net. States must now rely entirely on their economic performance to grow tax revenue.

- Federal Issue: The 40% “Sin Goods” tax is now a direct tax slab. Proceeds will be part of the Divisible Pool (shared with states via Finance Commission formula), unlike the Cess which was exclusively for compensation. This is actually a positive for fiscal federalism in the long run.

Issues, Challenges & Gaps in GST Structure and Implementation

- Vertical Fiscal Imbalance: The Centre collects the lion’s share of buoyant taxes (Income Tax, Corp Tax, huge GST share), while States bear 60%+ of general government expenditure (Health, Education, Police).

- The “Veto” in GST Council: The Centre’s 33% voting power means no resolution can pass without its support, while States cannot push a decision alone even with unanimity.

- Borrowing Constraints (NBC): The inclusion of off-budget borrowings in debt limits restricts States’ ability to fund capital-intensive infrastructure projects.

- Narrowing Divisible Pool: While the Sin Goods tax enters the pool, the Centre’s increasing reliance on Cesses and Surcharges (on other taxes like Petrol/Diesel) shrinks the net proceeds shared with States (Cesses are not shared).

- Standardization vs. Autonomy: A uniform tax policy (One Nation, One Tax) ignores regional disparities. A consumption state like Bihar benefits differently than a manufacturing state like Tamil Nadu.

- Delayed Transfers: Procedural delays in releasing GST shares continue to create liquidity crunches for States.

Government Initiatives

- Scheme for Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment: 50-year interest-free loans by Centre to incentivize State capex.

- Incentivized Borrowing: allowing extra borrowing (0.5% of GSDP) linked to power sector reforms.

Comparative Models

- Canada: Provinces have high tax autonomy; they can levy their own retail sales taxes alongside federal GST. (More Decentralized)

- Brazil: A complex system where states have significant power to set rates, leading to “tax wars.” (India avoids this chaos but loses autonomy).

- India’s Position: A unique “Cooperative Federalism” model where sovereignty is pooled. We are more centralized than Canada but more harmonized than Brazil.

Way Forward & Recommendations

- Strengthen the 16th Finance Commission: It must devise a formula that rewards fiscal prudence without penalizing states with higher legacy debts. It should recommend capping Cesses/Surcharges.

- GST Council Reform: A dispute resolution mechanism (independent of the Council) is needed, as originally envisioned in Art 279A, to adjudicate Centre-State disagreements.

- Differentiate “Debt”: Distinguish between borrowing for Capital Expenditure (creates assets, should be lenient) and Revenue Expenditure (salaries/subsidies, should be strict).

- Revenue Augmentation: States must tap into under-taxed avenues under their list: Property Tax, Agricultural Income (politically sensitive but necessary), and Stamp Duties.

Prelims Focus: Revision Facts & Traps

Key Institutions & Articles:

- GST Council: Chairperson is Union Finance Minister. Members are State Finance Ministers.

- Trap: It is a constitutional body (Art 279A), not statutory.

- Trap: Decisions are NOT binding on Parliament/State Legislatures in theory (SC judgment in Mohit Minerals case), but binding in practice for the harmonized system.

- Article 246A: Special provision for GST laws (overrides Art 246 to an extent).

- Article 269A: Levy and collection of GST on inter-state trade (IGST).

Important Data (New Structure):

- Slabs: 5% (Essentials), 18% (Standard), 40% (Demerit/Sin Goods).

- Exemptions: Unpacked food grains, fresh vegetables, essential services (health/education).

- Sin Goods: Aerated drinks, tobacco, luxury cars.

Likely MCQ Traps:

- Statement: “The GST Compensation Cess proceeds are part of the Consolidated Fund of India and are shared with states via the Finance Commission.”

- Correction: FALSE. (Pre-2025) They were credited to a non-lapsable fund in the Public Account and transferred directly to states. (Post-2025) The Cess is abolished; the new 40% tax IS shared.

- Statement: “States have no power to borrow from abroad.”

- Correction: TRUE. Under Article 293, states cannot borrow externally (foreign) without Centre’s consent/guarantee.

Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Mains:

- “The implementation of GST is a testimony to the cooperative federalism in India. Comment.” (GS II, 2017)

- “Explain the significance of the 101st Constitutional Amendment Act. To what extent does it reflect the accommodative spirit of federalism?” (GS II, 2017)

- “Discuss the rationale for introducing the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in India. Bring out critically the reasons for the delay in rollout for its regime.” (GS III, 2013 – Old but relevant for background)

- “How have the recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission of India enabled the states to improve their fiscal position?” (GS II, 2021 – Can be linked to 16th FC context)

Prelims:

- 2017: Question on the composition/functions of the GST Council.

- 2018: Question on the definition of GST and which taxes it subsumed.