Introduction: The Awakening of a Nation #

Imagine India in the late 19th century. The dust from the Revolt of 1857 had settled, but the silence that followed was not of contentment, but of introspection. The British Empire seemed invincible, a steel frame covering the subcontinent. Yet, beneath this surface, a tectonic shift was occurring. It wasn’t led by swords or sepoys this time, but by the pen, the press, and the courtroom. This is the story of how India began to define itself not as a collection of warring principalities, but as a Nation.

Part I: Factors for the Rise of Nationalism #

Why did nationalism rise? It wasn’t a gift from the British; it was a reaction to them. The British had unwittingly forged the tools for their own opposition. They built railways to move troops and goods, but these trains carried leaders and ideas from Punjab to Bengal, knitting the country together. They taught English to create clerks, but the Indians read Mill, Rousseau, and Mazzini, learning the language of democracy and rights.

But the real spark came from the “reactionary policies” of the rulers. Lord Lytton, the Viceroy in the late 1870s, acted like the villain of the piece. He organized a grand Delhi Durbar while the country starved in famine. He passed the Vernacular Press Act (1878) to gag Indian newspapers and the Arms Act (1878) to disarm the population.

Then came the Ilbert Bill Controversy (1883) under Lord Ripon. The Bill sought to allow Indian judges to try Europeans. The white community revolted with racial arrogance. This opened the eyes of the Indian intelligentsia: justice and fair play could not be expected where the interests of the European community were involved. The Indians learned a valuable lesson: to get what you want, you must organize.

Part II: Pre-Congress Associations: The Rehearsals #

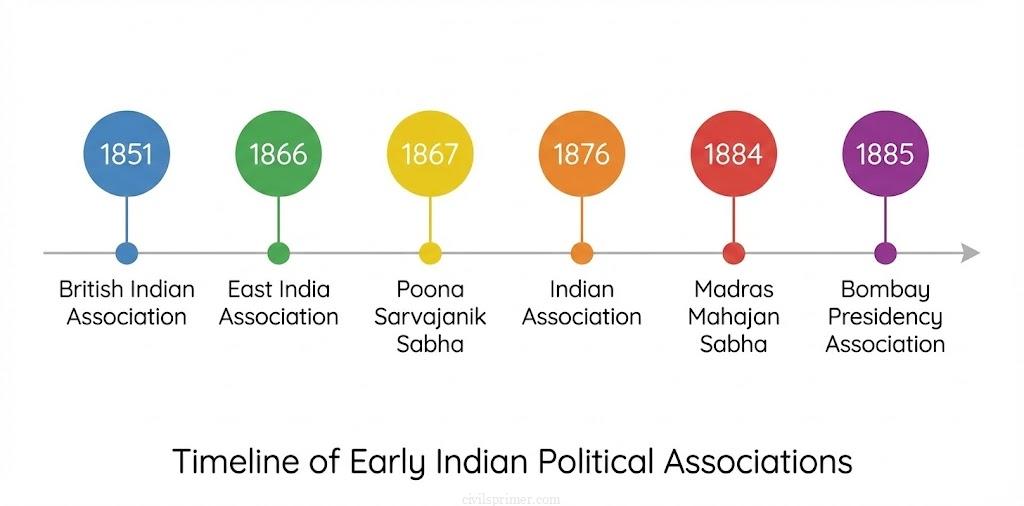

Before the grand stage of the Congress was set, there were rehearsals in the provinces. The early associations were dominated by wealthy aristocrats and landlords, but gradually, the educated middle class took over.

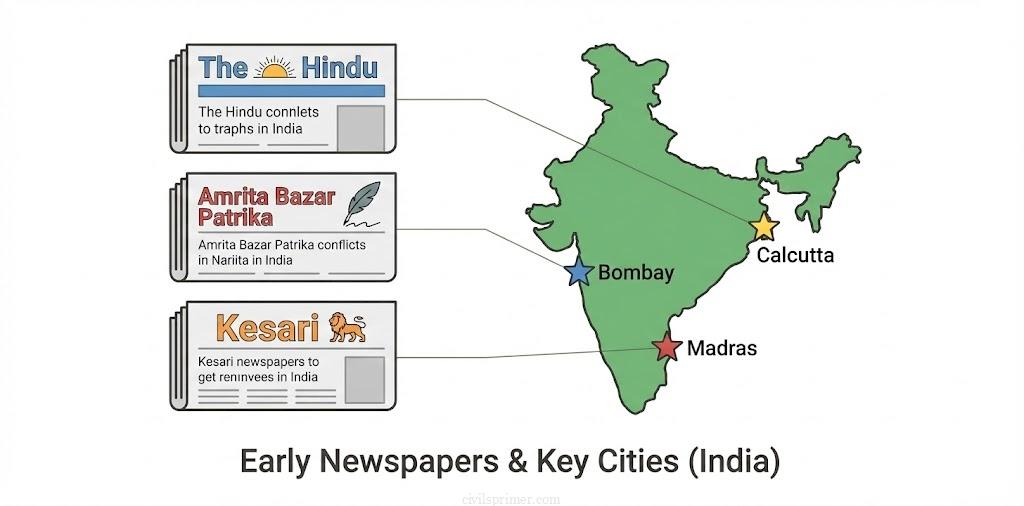

- In Bengal: The first political tremors were felt here. Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s associates formed the Bangabhasha Prakasika Sabha in 1836. Later, the British Indian Association (1851) fought for the rights of the landed gentry. But the real game-changer was the Indian Association of Calcutta, founded in 1876 by Surendranath Banerjea and Ananda Mohan Bose. They were the younger nationalists, discontented with pro-landlord policies. They agitated against the reduction of the age limit for the Civil Services examination, showing that an all-India movement was possible.

- In Bombay: The Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, founded in 1867 by Mahadev Govind Ranade, served as a bridge between the government and the people. Later, the Bombay Presidency Association (1885) was formed by the “trimurti” of Bombay—Pherozeshah Mehta, K.T. Telang, and Badruddin Tyabji.

- In Madras: The Madras Mahajan Sabha (1884) was founded by M. Viraraghavachari and G. Subramaniya Iyer to coordinate local associations.

All these rivers were flowing towards a single ocean. The need for an all-India organization was palpable.

Part III: The Birth of the Congress (1885) #

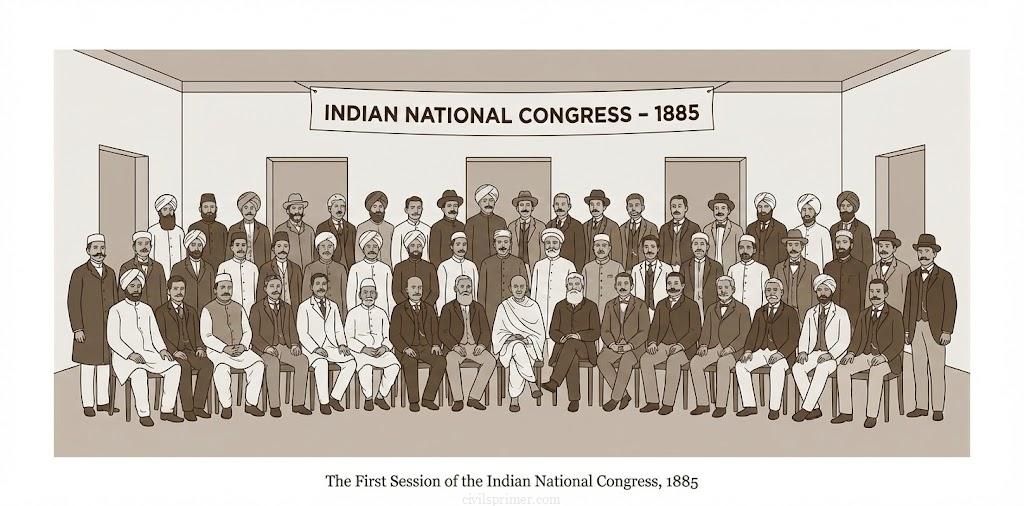

The stage was finally set in December 1885. The location: Gokuldas Tejpal Sanskrit College, Bombay. Seventy-two delegates from all over India met to form the Indian National Congress (INC). The first President was W.C. Bonnerjee.

The Mystery of A.O. Hume: Why was a retired British civil servant, Allan Octavian Hume, the main organizer? This birthed the “Safety Valve Theory”—the idea that the British Viceroy, Lord Dufferin, wanted a mild outlet for Indian discontent to prevent a violent 1857-style revolt. Extremist leader Lala Lajpat Rai later used this theory to attack the Congress. However, modern historians argue for the “Lightning Conductor Theory”. Early nationalist leaders like G.K. Gokhale knew that if Indians started such a movement alone, the British would crush it immediately. They used Hume as a “lightning conductor” to ward off official hostility. If Hume was the organizer, the government would be less suspicious.

Part IV: The Era of the Moderates (1885–1905) #

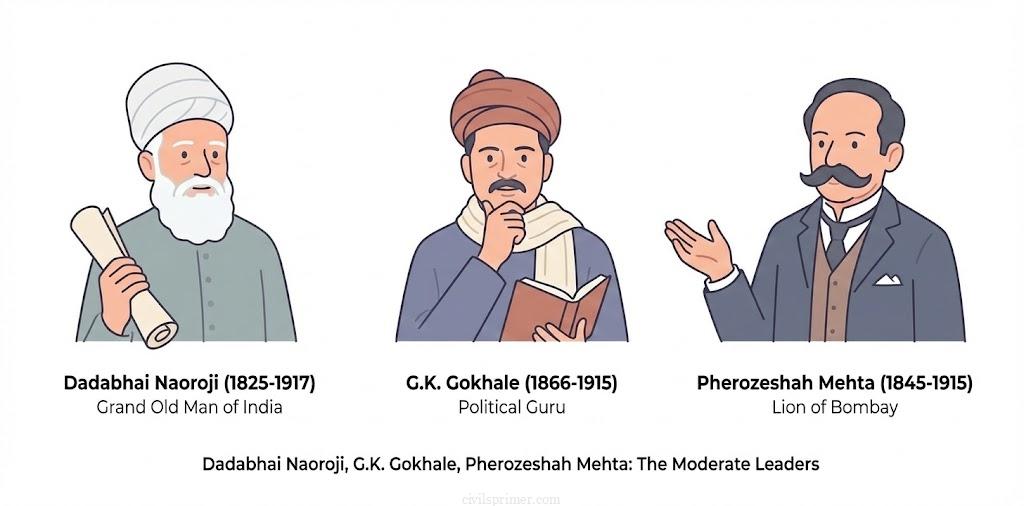

For the first twenty years, the Congress was dominated by leaders we now call the Moderates. These were men like Dadabhai Naoroji, Pherozeshah Mehta, D.E. Wacha, W.C. Bonnerjee, and S.N. Banerjea. They were staunch believers in liberalism and moderate politics.

Their Methods (The 3Ps): They did not believe in blood and revolution. Their weapons were the 3Ps: Petition, Prayer, and Protest. They worked within the constitutional framework. They held meetings, passed resolutions, and sent petitions to England. They believed the British were basically just but were unaware of the real conditions in India. Their goal was to educate the British public and political leaders.

What did they want?

- Expansion of Councils: They wanted Indians to have a say in how they were governed. Their agitation led to the Indian Councils Act of 1892, which allowed some indirect election (though the word “election” was avoided) and gave members the right to ask questions and discuss the budget.

- Indianization of Services: They demanded simultaneous Civil Services examinations in England and India and raising the age limit, arguing that Indian administration should be run by Indians.

- Civil Rights: They defended the freedom of speech and the press. The arrest of Bal Gangadhar Tilak in 1897 caused a nationwide outcry.

Part V: The Economic Critique – The Sharpest Weapon #

The Moderates may have been gentle in their methods, but they were savage in their intellectual analysis. This was their greatest contribution. Leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji, R.C. Dutt, and Dinshaw Wacha deconstructed the British Empire.

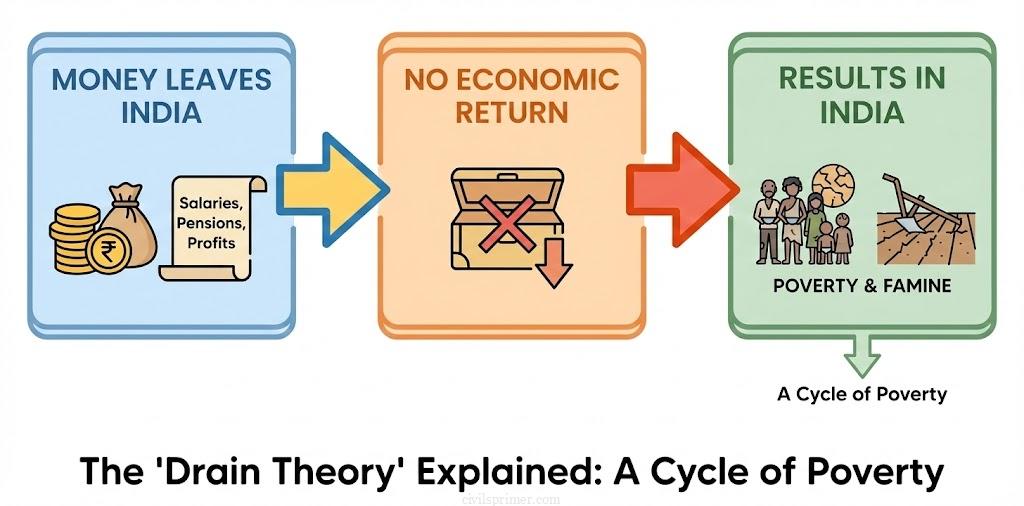

They put forward the “Drain Theory”. Dadabhai Naoroji, in his classic Poverty and Un-British Rule in India, argued that India wasn’t poor by nature; it was being made poor. Britain was draining India’s wealth—through salaries, pensions, and home charges—without giving anything in return. They showed that British policies were transforming India into a supplier of raw materials and a market for British manufactures, ruining Indian handicrafts.

They coined the slogan, “No taxation without representation”. By linking Indian poverty to British rule, they destroyed the moral foundation of the British Empire. They taught the Indian people that British rule was exploitative, not benevolent.

The Grand Finale: Limitations and Legacy #

Why did the Moderates fade? They failed to widen their base. They were mostly urban, English-educated elites—lawyers, doctors, and journalists. They lacked faith in the masses, believing the Indian people were not yet ready for a large-scale struggle. They did not organize mass movements.

However, we cannot judge them too harshly. As Bipan Chandra noted, “The period from 1858 to 1905 was the seed time of Indian nationalism; and the early nationalists sowed the seeds well and deep”. They built the foundation upon which the later mass movements of Gandhi were constructed. They turned a geographical expression called India into a political entity.

UPSC Mains Subjective Previous Years Question #

- 2021 → To what extent did the role of moderates prepare a base for the wider freedom movement? Comment.

- 2019 → Examine the linkages between the nineteenth century’s ‘Indian Renaissance‘ and the emergence of national identity.

- 2017 → Why did the ‘Moderates’ fail to carry conviction with the nation about their proclaimed ideology and political goals by the end of the nineteenth century?

- 2014 → Examine critically the various facets of economic policies of the British in India from mid-eighteenth century till independence.

Answer Writing Minors #

Introduction (For Mains Answers)

The period between 1885 and 1905, often termed the ‘Moderate Phase’ of the Indian National Congress, marked the organized beginning of the Indian freedom struggle. Dominated by an English-educated intelligentsia including leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji and G.K. Gokhale, this phase was characterized by a belief in constitutional methods and the British sense of justice, focusing on administrative reforms and the development of an Indian national consciousness.

Conclusion (For Mains Answers)

Although the Moderates were criticized for their narrow social base and “mendicant” politics, their greatest legacy was the economic critique of colonialism, particularly the ‘Drain Theory,’ which shattered the myth of British benevolence. By establishing the foundational arguments against imperial rule and training Indians in political work, they prepared the necessary groundwork for the mass-based movements that followed under the Extremists and Mahatma Gandhi.

Related Latest Current Affairs #

- November, 2025: 150 Years of “Vande Mataram” Celebrations The Prime Minister inaugurated year-long celebrations for the 150th anniversary of the national song “Vande Mataram.” Associated with the Swadeshi Movement (1905), the song became the lyrical soul of resistance, marking the transition from the Moderate era’s methods to mass mobilisation

- October, 2025: 150th Anniversary of Vande Mataram and Swadeshi Movement Link In his ‘Mann Ki Baat’ address, the PM highlighted the song’s role as a unifying mantra for 140 crore Indians. Historically, its adoption as a slogan during the anti-partition agitation of Bengal (1905) marked a pivotal shift in the freedom struggle, moving beyond the Moderate methods of petitioning

- August, 2025: 200th Birth Anniversary of Dadabhai Naoroji The nation celebrated the bicentenary of the “Grand Old Man of India,” a founding member and three-time president of the Indian National Congress (1886, 1893, 1906). He is credited with the “Drain of Wealth” theory, expounded in his work Poverty and Un-British Rule in India, which provided the economic critique of colonialism

- August, 2025: Tributes to Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak On his death anniversary, tributes were paid to Tilak, often called the “Father of Indian Unrest.” The event highlighted his ideological differences with the Moderates; he opposed their methods of “prayer and petition” and advocated for direct action and Swaraj as a birthright, leading to the Surat Split (1907)

- August, 2025: Commemoration of Sri Aurobindo Tributes were paid to Sri Aurobindo, a key figure in the rise of Indian nationalism who advocated “spiritual nationalism.” He was a vocal critic of the Congress’s early Moderate leadership, criticizing their “mendicant” policies before evolving into a spiritual leader

- June, 2025: 120th Anniversary of the Servants of India Society (G.K. Gokhale) The 120th anniversary of the Servants of India Society, established by Moderate leader Gopal Krishna Gokhale on June 12, 1905, was observed. The organization was founded to train national missionaries for the service of India in a religious spirit and to promote the country’s interests by constitutional means