From Traders to Masters: The Story of the British Conquest #

Imagine India in the mid-18th century. The mighty Mughal Empire is crumbling. Regional powers like the Marathas, Mysore, and Hyderabad are scrambling for dominance. In this chaotic political theatre, a group of foreign merchants—the British East India Company (EIC)—decides to step out of their warehouses and onto the battlefield. This is the story of how a trading company swallowed a subcontinent.

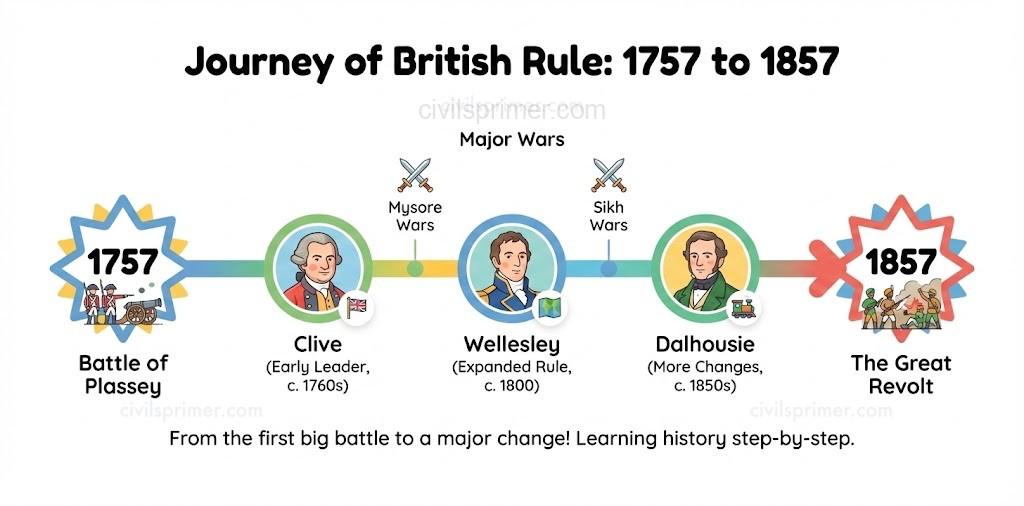

Act I: The Turning Point in Bengal (1757–1764) #

Our story begins in the richest province of India: Bengal. The young Nawab, Siraj-ud-daula, was furious. The British were misusing trade privileges (Dastaks) and fortifying Calcutta without permission. When they refused to stop, Siraj attacked and captured Calcutta in 1756. This led to the infamous “Black Hole Tragedy,” giving the British a moral excuse to retaliate. Enter Robert Clive. He didn’t just bring an army; he brought treachery. He forged a secret alliance with Mir Jafar (the Nawab’s commander), Rai Durlabh, and Jagat Seth (the richest banker).

The Battle of Plassey (1757): On June 23, 1757, the armies met at Plassey. It was hardly a battle; it was a transaction. A large part of the Nawab’s army, led by Mir Jafar, stood still. Siraj was defeated and killed. The British had won their first major foothold in India, not just by the sword, but by deceit. However, the thirst for revenue was unquenchable. Mir Jafar was replaced by Mir Kasim, who tried to be independent. He formed a grand alliance with Shuja-ud-Daula (Nawab of Awadh) and Shah Alam II (Mughal Emperor).

The Battle of Buxar (1764): This was the real contest. On October 22, 1764, the British forces under Major Hector Munro crushed the combined Indian armies. Unlike Plassey, this was a military victory, not a conspiracy.

The Aftermath: The Treaty of Allahabad (1765) changed everything. The Mughal Emperor granted the Diwani Rights (right to collect revenue) of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa to the Company. The traders had officially become administrators.

Act II: The Tiger of Mysore (1767–1799) #

While the British secured the East, a formidable power rose in the South: Mysore, under Haidar Ali and his son Tipu Sultan. They were the only Indian rulers who understood the importance of a modern army and a strong economy.

The conflict spanned four wars:

1. First Anglo-Mysore War (1767–69): Haidar Ali outmaneuvered the British and dictated the Treaty of Madras, forcing the British to promise help if Mysore was attacked.

2. Second Anglo-Mysore War (1780–84): The British failed to help Haidar against the Marathas, violating the previous treaty. Haidar forged an alliance with the Marathas and Nizam. Though Haidar died during the war (1782), Tipu continued the fight, ending with the Treaty of Mangalore.

3. Third Anglo-Mysore War (1790–92): Lord Cornwallis personally led the British army. Tipu was defeated and forced to sign the humiliating Treaty of Seringapatam, giving away half his kingdom and surrendering two sons as hostages.

4. Fourth Anglo-Mysore War (1799): Lord Wellesley arrived with an imperialist vision. Tipu refused to accept a Subsidiary Alliance. He died fighting at the gates of his capital, Seringapatam. Mysore became a dependency of the British.

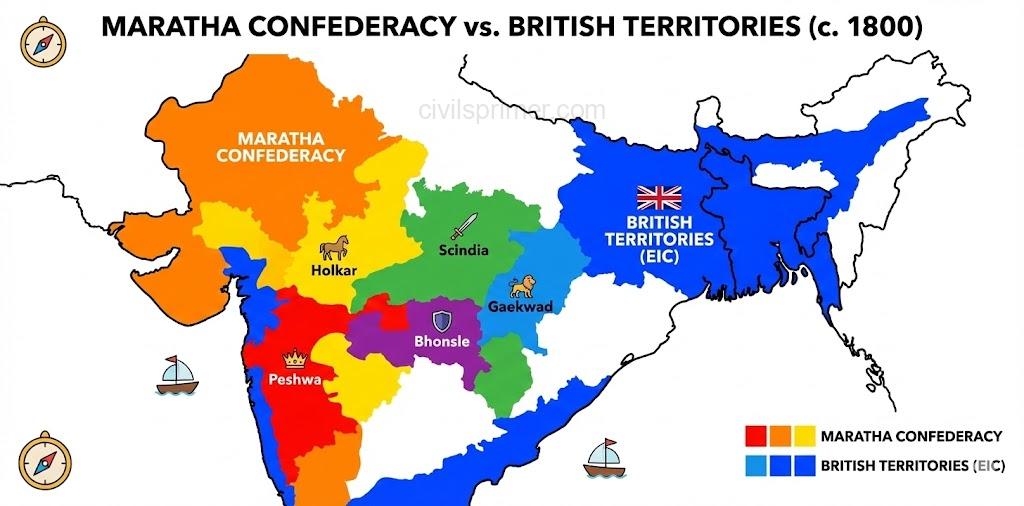

Act III: The Maratha Struggle (1775–1818) #

The Marathas were the strongest contenders to replace the Mughals. However, their internal disunity was their Achilles’ heel.

- First Anglo-Maratha War (1775–82): Triggered by Raghunath Rao’s ambition to become Peshwa. The British intervened but faced stiff resistance from Nana Phadnavis. It ended with the Treaty of Salbai, guaranteeing 20 years of peace.

- Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–05): The Peshwa Baji Rao II, defeated by Holkar, fled to the British and signed the Treaty of Bassein (1802), accepting the Subsidiary Alliance. This “gave the English the key to India”. Scindia and Bhonsle challenged this but were defeated by Arthur Wellesley.

- Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–19): A final desperate attempt by the Maratha chiefs to throw off the British yoke. They were crushed. The Peshwaship was abolished, and the Peshwa was pensioned off to Bithur (Kanpur). The British were now masters of the land south of the Vindhyas.

Act IV: Conquest of the North-West (1843–1849) #

The British obsession with a possible Russian invasion led them to look North-West.

- Sindh (1843): Despite treaties of friendship, Charles Napier annexed Sindh. He famously noted, “We have no right to seize Sindh, yet we shall do so, and a very advantageous… piece of rascality it will be”.

- Punjab (1845–49): The mighty Sikh army, built by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, fell into chaos after his death in 1839.

- First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–46): Ended with the Treaty of Lahore. The British resident became the virtual ruler.

- Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848–49): A revolt by Sikh governor Mulraj led to the final war. Lord Dalhousie annexed Punjab in 1849.

The Tools of Empire: How Did They Consolidate? #

The British didn’t just fight; they legislated.

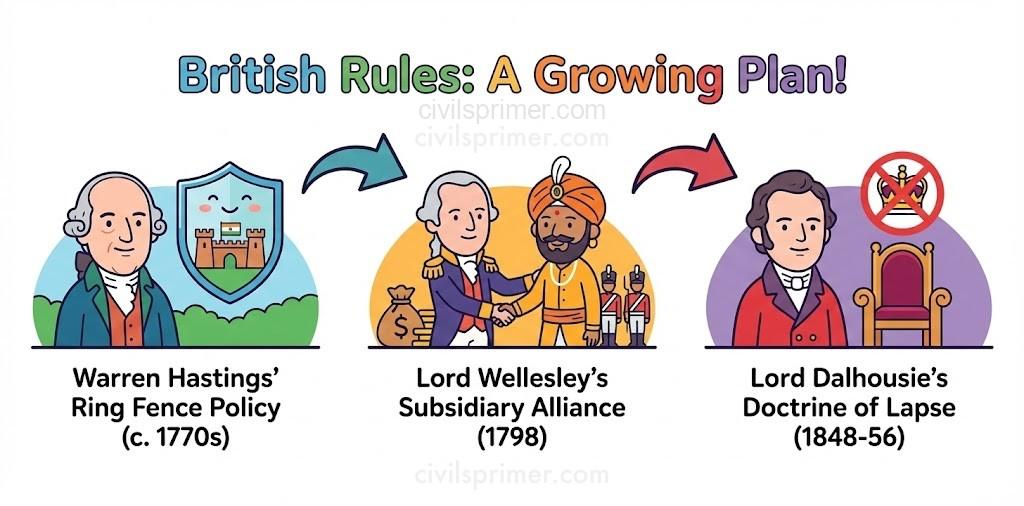

- Ring Fence Policy (Warren Hastings): Creating buffer states (like Awadh) to protect their own frontiers.

- Subsidiary Alliance (Lord Wellesley, 1798): A masterstroke. Indian rulers had to station British troops in their territory and pay for them. They lost the right to an independent foreign policy. It disarmed Indian states without a war. The Nizam of Hyderabad was the first to sign (1798).

- Doctrine of Lapse (Lord Dalhousie, 1848-56): If a ruler died without a natural male heir, his state would “lapse” to the British; adopted heirs were not recognized. Satara, Jhansi, and Nagpur were swallowed up by this policy.

By 1857, the East India Company had transformed from a trading corporation into the paramount power of the Indian subcontinent, setting the stage for the massive eruption of 1857.

UPSC Mains Subjective Previous Years Questions #

- 2022 → Why did the armies of the British East India Company – mostly comprising of Indian soldiers – win consistently against the more numerous and better-equipped armies of the Indian rulers? Give reasons.

- 2017 → Clarify how mid-eighteenth-century India was beset with the spectre of a fragmented polity.

Answer Writing Minors #

- Introduction (For Mains Answers): The mid-18th century in India was a period of transition characterized by the decline of the Mughal central authority and the rise of autonomous regional powers. Into this political vacuum stepped the British East India Company, whose transformation from a mercantile entity to a sovereign power was facilitated by superior military strategy, diplomatic policies like the Subsidiary Alliance, and the internal fragmentation of Indian polities.

- Conclusion (For Mains Answers): Ultimately, the British conquest was not merely a result of military superiority but a combination of strategic alliances, economic strength derived from control over Bengal’s revenue, and a disciplined administrative structure. By systematically eliminating European rivals and subduing indigenous powers through policies like the Doctrine of Lapse, the Company consolidated its paramountcy, fundamentally altering the subcontinent’s history.

Related Latest Current Affairs #

- October 2025: Revisiting the Anglo-Nepalese War and Treaty of Sugauli Amidst political turmoil in Nepal, discussions on India-Nepal relations referenced their historical foundations, specifically the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814–16). The war concluded with the Treaty of Sugauli (1816), which defined the modern boundary between Nepal and British India, initiating the recruitment of Gorkhas into the British (later Indian) Army.

- July 2025: UNESCO World Heritage Status for Maratha Military Landscapes The “Maratha Military Landscapes of India,” comprising 12 forts like Raigad and Gingee, were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. These forts showcase the strategic defence systems developed by the Marathas, who were key adversaries of the British during the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775–1818).

- July 2025: Controversy Over Paika Rebellion Omission in Textbooks A political backlash occurred after NCERT textbooks omitted the Paika Rebellion (1817). Led by Bakshi Jagabandhu in Odisha, this armed uprising against British colonial rule and land revenue policies is often cited by the Odisha government as the “First War of Independence,” predating the 1857 revolt.