The Great Game of the Seas: How Europe Came to India #

Imagine the late 15th century. The land routes to the spice-rich East are blocked by the Ottoman Turks. Europe is desperate for pepper, cinnamon, and the riches of the Orient. In this desperation, a race begins—a race that would change the destiny of the Indian subcontinent forever.

Act I: The Portuguese – The Pioneers of the Ocean #

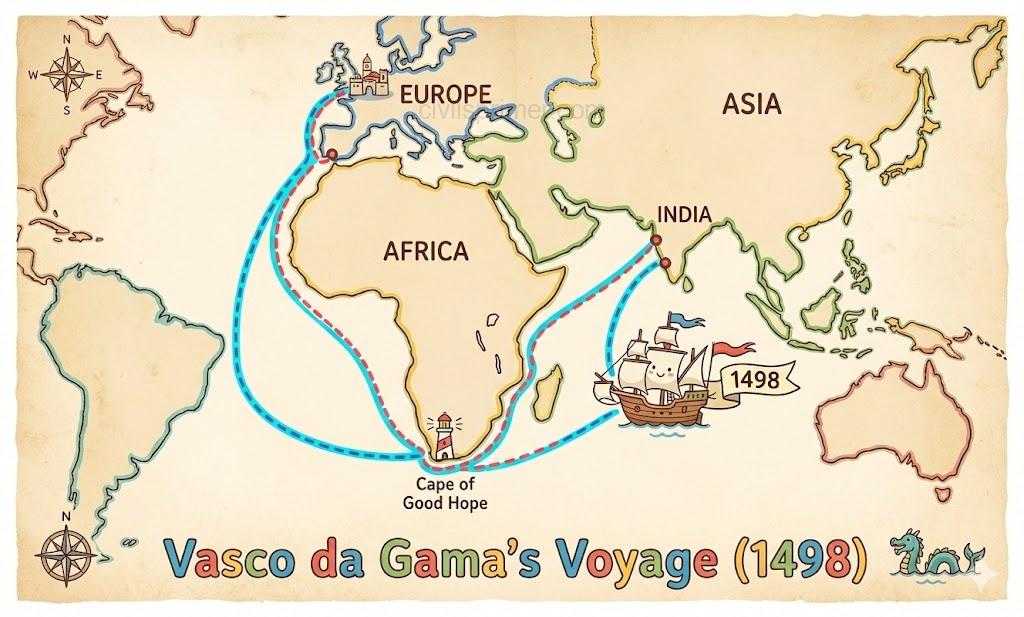

The story begins not with the British, but with the Portuguese. In 1498, a fleet led by Vasco da Gama landed at Calicut. He was welcomed by the Hindu ruler, the Zamorin, though the Arab traders on the shore looked on with suspicion. Vasco returned to Portugal with a cargo worth sixty times the cost of his voyage, sparking a frenzy in Europe.

The Portuguese didn’t just want to trade; they wanted to rule the seas. They appointed Francisco de Almeida as the first Governor in 1505. He initiated the “Blue Water Policy” (Cartaze System), believing that whoever controlled the sea controlled India. However, the real builder of the Portuguese power was Alfonso de Albuquerque. In 1510, he captured Goa from the Sultan of Bijapur—the first bit of Indian territory to fall to Europeans since Alexander the Great.

Why did they eventually fail? They were intolerant. Their zeal to convert locals to Christianity and their piratical activities made them unpopular. Furthermore, the discovery of Brazil diverted their attention to the West. By the 17th century, their power had dwindled to just Goa, Daman, and Diu.

Act II: The Dutch – The Spice Seekers #

Next came the Dutch. Formed in 1602, the Dutch East India Company was purely profit-driven. They established factories in Masulipatnam (1605), Pulicat, and Surat. However, the Dutch were more interested in the Spice Islands (modern-day Indonesia) than in India. After their defeat by the English in the Battle of Bedara (1759), they quietly bowed out of the Indian political game to focus on the Malay Archipelago.

Act III: The English – The Merchant Empire

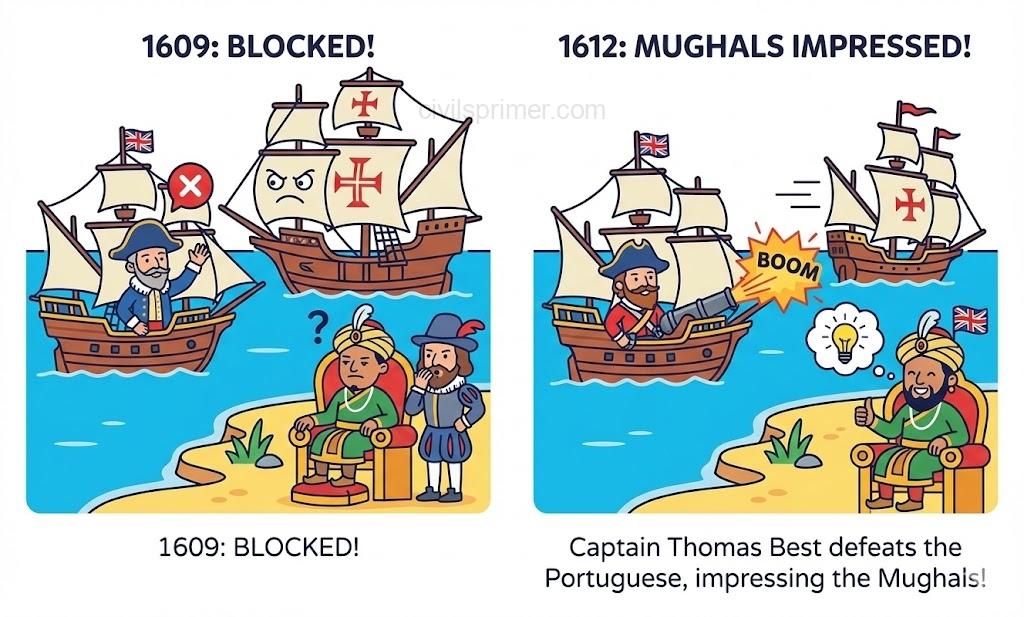

The real protagonist of our story, the English East India Company (EIC), was formed on December 31, 1600, via a Royal Charter by Queen Elizabeth I. Their entry was humble. Captain William Hawkins arrived at Jahangir’s court in 1609 but was blocked by Portuguese intrigue. It wasn’t until Captain Thomas Best defeated the Portuguese naval fleet off the coast of Surat in 1612 that the Mughals were impressed.

Sir Thomas Roe arrived in 1615 and secured permission to set up factories at Agra, Ahmedabad, and Broach. The English were patient. They built fortified settlements: Fort St. George in Madras (1639), Bombay (received as dowry by King Charles II in 1662 and leased to the Company), and Fort William in Calcutta (1690s). In 1717, they secured the Magna Carta of their trade—a Farman from Emperor Farrukhsiyar allowing duty-free trade in Bengal.

Act IV: The French – The Late Bloomers #

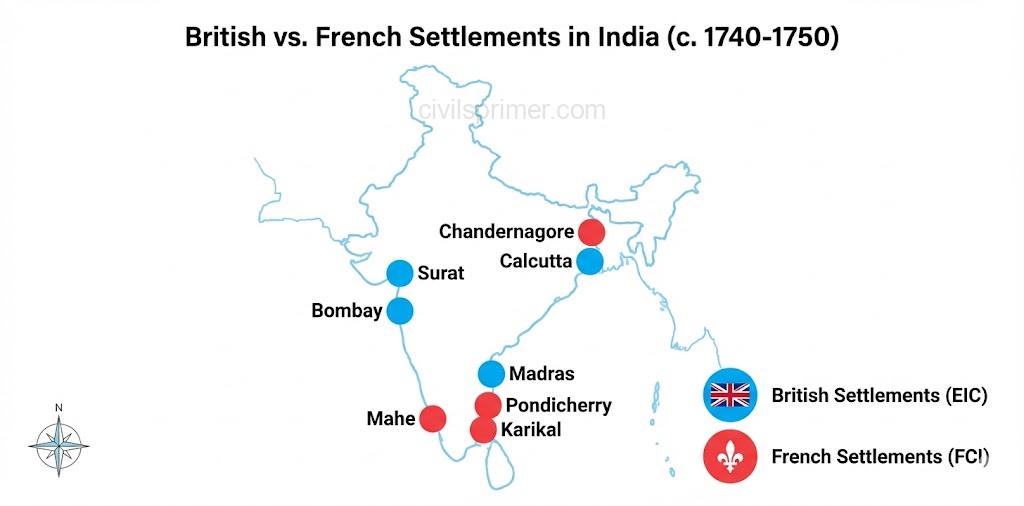

The last to arrive were the French in 1664, led by Colbert under Louis XIV. They established their stronghold in Pondicherry in 1674. For nearly a century, the English and French traded side-by-side. But as the Mughal Empire fractured in the 18th century, both companies realized that to protect their profits, they needed political power. This ambition set the stage for the fierce Carnatic Wars.

The Carnatic Wars: The Clash of Titans #

The Carnatic Wars were essentially the Indian theater of the global rivalry between Britain and France.

- First Carnatic War (1740–48): Triggered by the Austrian War of Succession in Europe. The French, led by Governor Dupleix, captured Madras. It ended with the Treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle, restoring Madras to the English.

- Second Carnatic War (1749–54): This was a proxy war. Dupleix interfered in the succession disputes of Hyderabad and Carnatic, supporting his own candidates. Initially successful, the French were eventually outsmarted by Robert Clive, who captured Arcot. The war ended with the Treaty of Pondicherry, and the visionary Dupleix was recalled to France—a fatal error for French ambitions.

- Third Carnatic War (1758–63): Triggered by the Seven Years’ War in Europe. The decisive battle was fought at Wandiwash (1760), where English General Eyre Coote routed the French army.

Result: The Treaty of Paris (1763) clipped France’s wings. They were allowed to keep their factories but forbidden from fortifying them or keeping troops. The English were now the masters of the subcontinent.

Why did the British Succeed? #

How did a trading company from a small island nation conquer the Indian subcontinent?

- Structure of the Company: The English EIC was a private joint-stock company managed by a board of directors. It was enterprising and financially sound. The French Company was a state department, burdened by bureaucratic red tape and dependent on the whims of the French monarch.

- Naval Superiority: The Royal Navy was the most powerful in the world, allowing Britain to keep their supply lines open while cutting off the French.

- Industrial Revolution: Britain was the first to industrialize. They had the funds, the machinery, and the modern weaponry (muskets and cannons) that Indian powers lacked.

- Stable Government: While Europe was rocked by the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars, Britain had a stable government and a unified objective.

- Focus on Trade: Unlike the Portuguese or French who often prioritized religious conversion or territorial glory, the British never lost sight of their primary goal: profit. This ensured they always had the financial resources to fund their wars

UPSC Mains Subjective Previous Years Questions #

- 2022 → Why did the armies of the British East India Company – mostly comprising of Indian soldiers – win consistently against the more numerous and better-equipped armies of the Indian rulers? Give reasons.

- 2017 → Clarify how mid-eighteenth-century India was beset with the spectre of a fragmented polity.

- 2014 → The third battle of Panipat was fought in 1761. Why were so many empire-shaking battles fought at Panipat?

Answer Writing Minors #

- Introduction (For Mains Answers) : The mid-18th century in India was a period of transition characterized by the decline of the Mughal central authority and the rise of autonomous regional powers. Into this political vacuum stepped European trading companies, most notably the British and the French, whose commercial rivalries rapidly evolved into a struggle for political supremacy, fundamentally altering the subcontinent’s history.

- Conclusion (For Mains Answers): Ultimately, the British success was not merely a result of military superiority but a combination of strategic alliances, economic strength derived from the Industrial Revolution, and a disciplined administrative structure. By eliminating European rivals and subduing indigenous powers, the East India Company transformed from a trading entity into a sovereign power, ushering in the colonial era in India.

Related Current Affairs #

- October, 2025: Correction of Colonial Narratives at Sarnath The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) announced the installation of a new plaque at Sarnath to credit local ruler Babu Jagat Singh (1787-88) for the site’s rediscovery. This move aims to correct the historical narrative that previously attributed the discovery solely to British officials like Alexander Cunningham.

- October, 2025: Loan of Vrindavani Vastra from British Museum The British Museum agreed to loan the 16th-century Vrindavani Vastra to Assam for an exhibition. This rare textile, depicting the Vaishnavite Bhakti movement, was acquired during the colonial era and later cataloged in London, highlighting the flow of Indian artifacts to Europe during the period of European expansion.

- July, 2025: Revival of Machilipatnam Port’s European Trade Legacy The construction of a new greenfield port at Machilipatnam has revived interest in its history as a major 17th-century trade hub. The city was a key location where the Dutch, British, and French established their early factories and textile trade posts to export muslin and chintz to Europe.

- February, 2025: Renaming of Fort William to ‘Vijay Durg’ The historic Fort William in Kolkata, the headquarters of the Eastern Command, was renamed “Vijay Durg” to shed colonial legacies. Originally built by the British East India Company in 1696 and reconstructed by Robert Clive after the Battle of Plassey (1757), the fort symbolised the consolidation of British power in Bengal.

- January, 2025: Commemoration of Goa’s Struggle against Portuguese Rule The contributions of freedom fighter Libia Lobo Sardesai were honoured, bringing focus to the liberation of Goa from Portuguese control. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to establish a colony in India and the last to leave (1961), maintaining control for over 450 years.

- January, 2025: Colonial Origins of the Civil Services Discussions on the “Colonial Steel Frame” traced the historical evolution of the civil services to the East India Company’s patronage system (pre-1854). It highlighted the transition from company nominees trained at Haileybury College to the merit-based system introduced under British rule to administer their expanding territories.